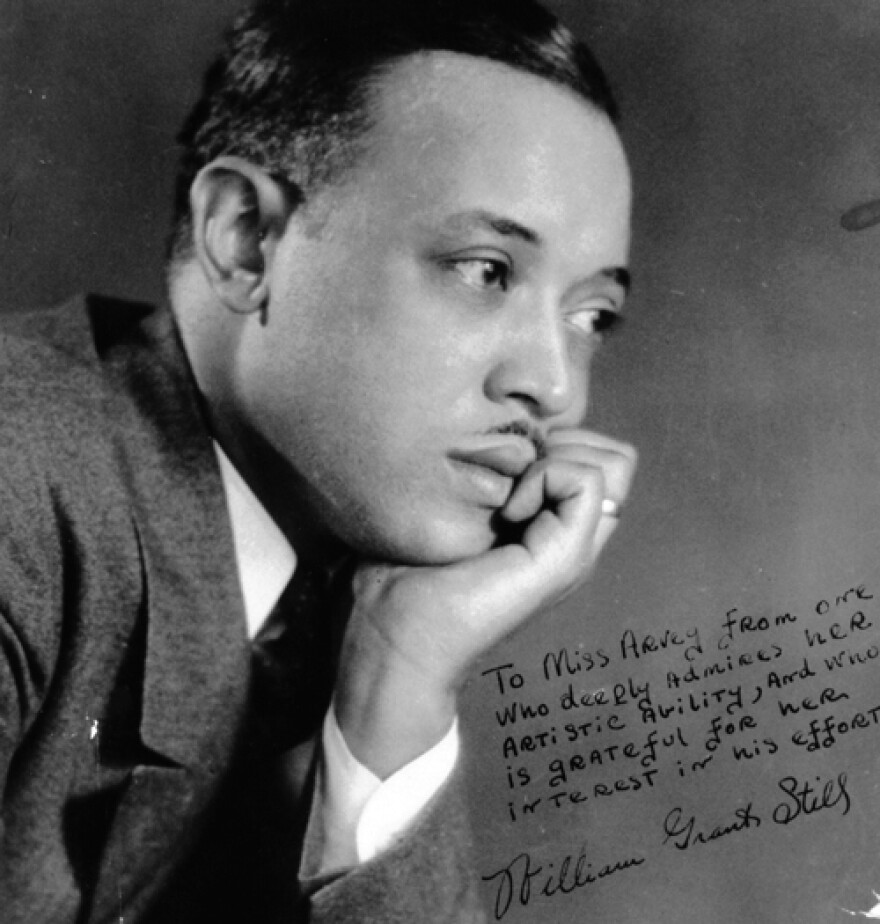

We call William Grant Still “The Dean of African-American Composers,” and the description strikes us as quaint. Not wrong, since it’s undeniable that Still was the leading Black American composer of concert music (although he opposed the term Black as one that divided people into false groups).

It’s the “Dean” part that surprises; it’s that we thought, at one time, that it was important to come up with titles for artists. Walt Whitman strives with William Cullen Bryant as "The Father of American Poetry," Emily Dickinson is “The Mother of American Poetry," Ralph Waldo Emerson and Mark Twain have both been called "The Father of American Literature," and Aaron Copland was indeed “The Dean of American Composers.” Maybe the U.S. is too grown up now to acknowledge Fathers, or maybe we’re too smart to have Deans, but we once thought it useful to expend serious effort on such judgments.

Today, the best we can do is to call someone an Idol, or A-List, or just Big: terms no deeper than a dollar bill.

http://youtu.be/mRkBrKFB0sY

So just how Big is William Grant Still? He came out of Mississippi to become the first African-American to conduct a major American orchestra, the first to have a large orchestral work played by a major American orchestra, and the first to have an opera produced by a major American company. He left Oberlin without a degree, for the East, to music-theater arranging and playing jobs, and his potential was immediately seen. Musicians as diverse as George Chadwick, W.C. Handy, Paul Whiteman, Artie Shaw, and Edgard Varèse recognized his talent.

It was the avant-garde Varèse who encouraged his composing the most, and who recommended his pieces for new-music concerts and publication. Still would later score for films (Pennies from Heaven), for TV (Perry Mason, Gunsmoke), and would compose more than 150 concert works, including ballets, operas, and symphonies.

It was his first symphony, the “Afro-American,” that brought him renown. Howard Hanson premiered it in 1931 with the Rochester Philharmonic, and Hanson would continue to champion Still’s music throughout his life. The symphony is based on blues, which Still felt was uniquely African-American, more so than spirituals, which he believed had become too commercialized.

Still had mixed feelings about the modernist Dismal Swamp. But it’s an evocative picture of the desperate life of the escaped slaves who found refuge in the Great Dismal Swamp, that wilderness spanning North Carolina and Virginia. In Danzas de Panama, for string quartet, string quintet, or string orchestra, he branches out to ethnicities not his own, which, he believed, was what any composer rightly does.

During his stellar career, William Grant Still became not only a leading African-American composer, but a leading American composer. He felt that music—his or anyone’s—should lift up people of all countries, colors, and races. A dean is a senior, respected leader. William Grant Still earns the title.

PROGRAM:

William Grant Still (1895-1978): Danzas de Panama (1948)

Dismal Swamp (1936)

Symphony No. 1, “Afro-American” (1930)

On the first Saturday of the month Jack Moore and I host Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection on WRTI 90.1 FM in Philadelphia and on the all-classical webstream at wrti.org. We also broadcast encore presentations of the entire Discoveries series (now 11 years and counting!) every Wednesday at 7 pm on WRTI HD-2. Look at an archive of all the shows here.