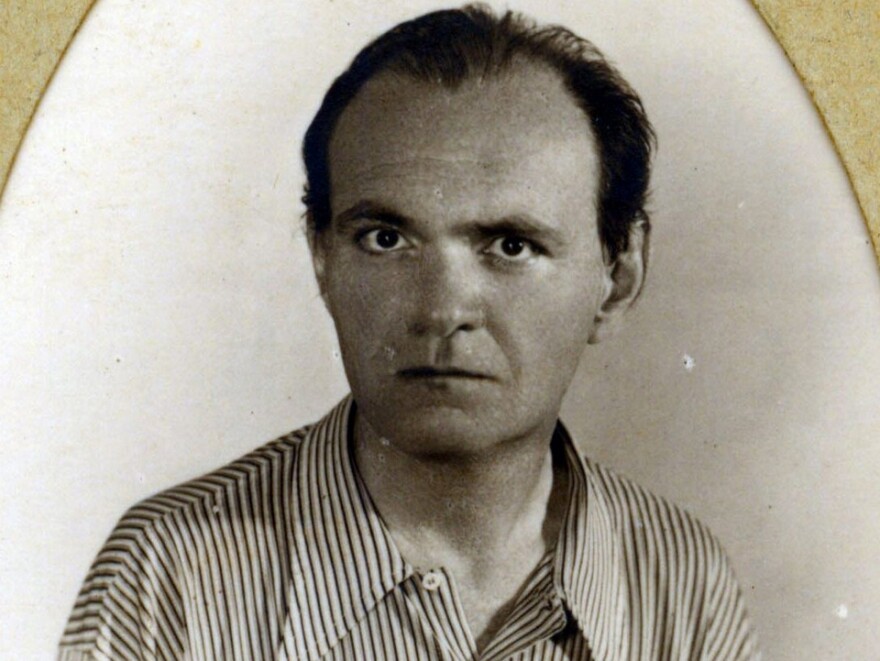

Music by an Austrian composer killed in the Holocaust surfaced in Buffalo, New York in 2001, and has been recorded by JoAnn Falletta leading the Buffalo Philharmonic. WRTI’s Susan Lewis talked with JoAnn Falletta about the life of Marcel Tyberg, the incredible story of how she discovered his music, and her passion about bringing it to life.

Austrian composer Marcel Tyberg was living in Northern Italy (now Croatia) in the early 1940s, composing dance music for a local hotel, playing church organ, teaching, and composing serious music as well.

A devout Catholic, his great great grandfather had been Jewish. Anticipating trouble when the Nazis invaded in 1943, Tyberg gave manuscripts of his more serious music to an Italian physician friend named Milan Mihich, whose son studied music with the composer.

Tyberg was arrested, deported, and died at Auschwitz on December 31, 1944. His music remained safe with the Mihich family, who themselves had to flee when the communists took control of the region.

Decades later, Mihich’s son, Dr. Enrico Mihich—a specialist in cancer research in America—delivered the music to JoAnn Falletta, music director of the Buffalo Philharmonic. She shared the incredible story:

Susan Lewis: How did you finally learn of Marcel Tyberg’s music?

I realized this was going to be a daunting project, but there was something about his urgency.

JoAnn Falletta: One day, maybe a couple of years after I became music director; I remember it was a terribly rainy day in Buffalo, and I got off the stage after rehearsal and standing at the door of my dressing room was this older gentleman, just drenched, wearing a raincoat, dripping water, carrying a shopping bag. I had never met him before.

It was Dr. Enrico Mihich [the son of Milan Mihich].

He said, “I have to speak to you. It’s very important.” He was the kind of person, when he said it was very important, you listened to him.

We went into my dressing room. He told me that story. He said, I know this is wonderful music. It’s great music. It needs to be played. I’ve tried with every music director and they haven’t been able to do it.

I looked at the music and I knew why they said no. It was almost illegible. The score had been handwritten, the pages were frayed, pieces were missing. It was almost impossible to read this European handwriting.

I realized this was going to be a daunting project but there was something about his urgency. He said to me, “I’m not going to live much longer. This is my life's mission to bring this music to life.”

And I thought, how could you not be moved by the belief in this composer that this man had?

So I took it home and it took me a long time to make anything out of it; peering at it, getting used to the way the handwriting took shape. But I had the feeling this was something quite special. So we had it put into a computer so we could print parts.

So you had this stack of handwritten manuscripts? How many different works?

I didn’t want to have all of these manuscripts in my possession. I said, give me the three symphonies. Don’t give me the masses with organ or chorus, or the chamber music right now. Let me look at the symphonies. And I started with the last, the 3rd, figuring he was at his most mature. And it was something really very special.

I remember looking at the opening, which starts with strings and a tenor tuba, much like Mahler. I thought this was like a link between Bruckner and the future, or what would have become the future.

He was certainly not writing 20th century aggressive new style music. No. He was looking back to the composers he had studied in Austria. Bruckner, Schumann, even Mendelssohn a little bit. Largely Bruckner but some Mahler as well.

We embarked on the very long journey of bringing this to life. This symphony had never been played. It was riddled with things we could only guess at: What note is that? How long should we hold that? What instrument? There are a lot of things where we had to be a detective.

Then when we took it to the [Buffalo Philharmonic]. I have to give them credit. They were willing to be part of this investigative project. They were looking at parts that in some places were not clear, didn’t quite make sense….Little by little, we played things together, trying to figure it out.

Finally we had it to the point where we could make a statement that was very close to what the composer had in mind.

It’s music of great nobility, great sweep, beautiful harmonic structure, and a kind of broad pacing like Bruckner. I am always reminded of Bruckner when I hear it, and reminded of Tyberg when I listen to Bruckner. There’s a real connection there for me.

So we played it and we recorded it. I think for all of us, it was really a journey of love. We got so much more than we thought we would. We didn't know really what this would be. It is music that is very individual, very strong and very special.

So you were driven at the beginning by the story of the man, but then once you started learning the music, you were also driven by...

By the music itself. Yes, and I think the orchestra felt the same way. It’s the kind of thing where you listen to the music around you, and the hairs on your arm rise up and it’s like wow! This is something truly beautiful.

It was never played in Europe at all?

Never played. He left Austria when his father died. His parents were both musicians, but he left Austria when his father died and moved to Italy with his mother. Basically to find work, and he did find work.

The whole area was and probably still is a vacation spot. It's extraordinarily beautiful, the sea side there. He worked partly writing popular music for the hotel which is still there; writing tea dance music – waltzes, polkas, for the tourists who would come from all over Europe. There were wealthy people who lived there. So he had the possibility of teaching their children.

So he and his mother settled there. I think they felt very safe in Italy. It wasn’t as in the middle of the war as other places until the Nazis invaded, and even then I think they didn’t feel threatened. When his mother heard the decree that said you must declare all of your relatives, any Jewish parentage, she did not feel in danger. She felt she just had to obey the law. She thought if she obeyed the law, she would not get in trouble. So she registered him. And of course that was like sealing his death warrant, but they didn’t know.

It was only after she died, and things began to be worse, that he had the feeling that this might not end well, or at least that his life was going to be disrupted by this. Hoping that he would get back to his work and his students.

He didn’t have any children?

No, he was single. Henry [Enrico] Mihich always felt he was in love with the sister of Rafael Kubelik who was a family friend. Not in Italy but when they were in Austria. Kubelik actually did play the second symphony with the Czech Philharmonic. But we can find no record of that.It was prewar. I’m sure most of what was there has been destroyed.

But he knew—because Tyberg told him—that the 2nd symphony had been played with the Czech Philharmonic. That was a big moment for him. But never again. And the 3rd symphony was not played. They were both written in Italy, and they didn’t have the means or even an orchestra to play it.

So you gave the world premiere of the 3rd symphony?

We did. That was in Buffalo. And we were asked to come to Croatia, where he lived, which is now Croatia and to perform in the theater in that little town. We did the second symphony, which is slightly smaller than the 3rd symphony which is big and very challenging. It was very moving To be in the theater where he gave concerts, heard concerts, and where he lived; and to visit the cemetery where his name is listed on the list of Jewish people who perished from that town. And Dr. Mihich came back with me there.

What year did you start playing his music?

The first performance was 2008. So from 2001 or 2 to get to the first performance, it took us about 5 years, to raise the money, to have someone input it, to talk to Naxos about it. Naxos was very excited about it.

This was funded by the Marcel Tyberg Musical Legacy Project?

It was. That was by Peter Fleischmann of the Foundation for Jewish Philanthropies in Buffalo. They raised money for this project. They made it possible to have all this work done.

There is a lot of music I understand.

There is. Not all of it is orchestral. The first symphony is kind of explorative symphony, where someone is writing a symphony to get the feeling of it. The leap to 2nd and 3rd were extraordinary. There are masses accompanied by organ; there’s wonderful chamber music; a sextet, a trio which we’ve recorded as well. That’s very poignant, and I think one of his great pieces.There is a collection of songs we’re hoping to issue on disc for voice and piano.

But he was still young when he died. So there’s a lot more music we would have had if he had not been murdered.

I went to Auschwitz to bring the CDs there. We have some record that that's where he died. I felt so overwhelmed that I could not leave them there. I just felt that nothing could make up for someone being in that place. The horror of that place. Nothing could make up for that. The people I was with were encouraging me and I said no, nothing could make up for it. So I didn’t do it.

The next year Peter and Ilene Fleischmann took it and put it in a sacred place where they have a museum of people who went through there and died there. I know it's there now and I’m glad they were able to do that.

So through this project his music is experiencing rebirth and in some cases birth.

That’s right.

And the details about his life—are they mostly coming from the son – Dr. Mihich?

Yes, when we went to Croatia we tried to find people who knew him. We found people who said their father or grandfather knew him. They said he was a great musician and taught music.

Most of the people knew him publicly as the person who wrote music for the dance bands and the church organist. Those were his two big jobs. And a music teacher. So he was the quiet music teacher who did these other things.

His serious music I think he only shared with very few people. That was his secret life. He was writing these symphonies, these masses, maybe never really expecting them to be played; hoping, but he was not really known as a person who was writing concert music.

And is Dr. Mihich the son still around?

No, he died a couple of years ago. He was an extremely accomplished man in terms of cancer research. Lauded all over the world, he would travel and talk about his profession all over the world.

But in a way I think the final realization of bringing this music back to the world was the great moment of his life. Not only had he fulfilled his promise to this father, but he had done something extraordinary for his teacher whom he truly seemed to love.

It sounds as if you've become pretty passionate about it, too.

Oh, I am very passionate about the music. And for me, it is a reparation. We can never take away one moment of horror, not one moment of pain. But for someone like Tyberg, we can do for him the thing that was dearest to him, and that was to have his music heard. That would have been his life's desire. It makes us feel we are accomplishing something beyond making a CD.

I was listening to the 3rd symphony. I was struck by the beauty of the music; you don’t have any inkling of the horrible things going on around him.

Right. It's about the beauty of the music. And of course, patterning himself after Bruckner and Schumann. Especially Bruckner, the kind of spirituality he had, I think he was following that. Music was meant to be beautiful. Yes there are moments of darkness in there. But he was not affected by the net of terror that was probably growing around him. I think like most people he could probably not believe it would get to that point.

There he was in this beautiful, safe tourist city where he taught music lessons and was known by everyone in the town. What could be safer than that?