On Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection, Saturday, 5-6 pm... One hundred years ago, and the world was in upheaval. The 19th century was fast becoming a memory by 1915. The previous generation’s nationalism in classical music had catapulted new languages into the concert hall, but it was now seen as irrelevant, corrosive, or at best, old-fashioned. Nationalism was now viewed through the War, in its second year, called “Great” by some and “World” by others. In a few decades it would take on a name even more horrible than World War; it would be called the “First.”

Two very different composers who died in 1915 signify the passing century remarkably well. One was the friend of royalty; another, the friend of musical royalty.

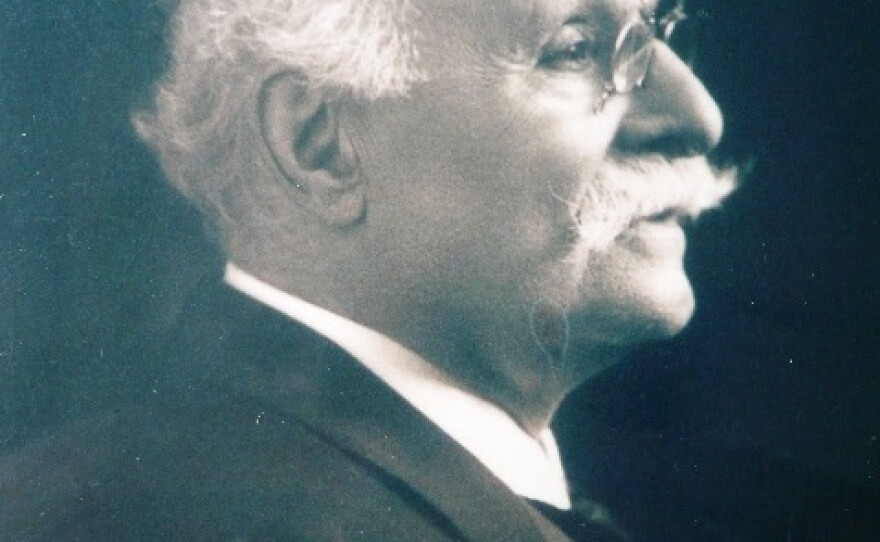

Émile Waldteufel’s violinist brother Léon won admission to the Paris Conservatory, and the father Louis moved the entire family there, from Strasbourg in the Alsatian region of France. It was a smart move, for Louis Waldteufel conducted his own successful orchestra, and found even more fame in the country’s capital city. Émile went on to study piano at the Conservatory, soloed with the Waldteufel Orchestra, and at 27, became the court pianist for Empress Eugénie.

Two very different composers who died in 1915 signify the passing century remarkably well. One was the friend of royalty; another, the friend of musical royalty.

But the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 greatly altered royal life. Waldteufel continued to play for small elite gatherings but was otherwise little-known. The Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII), however, attended one of those events, loved a little waltz he heard, and invited the piano-playing composer, ÉmileWaldteufel, to London. It was there that he became famous, writing dances that are still heard today, including Les Patineurs, or The Skater Waltz. He composed and conducted throughout Europe and retired to Paris. After a hugely successful career, he died when Debussy and Stravinsky were au courant.

Sergei Taneyev was also a pianist—a brilliant one—and a music critic and voracious scholar of seemingly any subject that came along. Mathematics, philosophy, science, and history all came under his intense interest, but it was composition that was his dearest love. It expressed itself for him in rigorous counterpoint, the exacting placement of note against note and line against line. Large washes of sound or simple folk tunes evoking a Russian mythos little interested him. Bach and Mozart were to be revered.

Tchaikovsky, 16 years older than Taneyev and one of his best friends, nevertheless feared his criticism. The world-famous composer would ask him sincerely to tell him what he thought of a certain work, and Taneyev obliged, in brutal frankness. He rubbed other composers the wrong way, but his friendship with Tchaikovsky remained undiminished, if needing, here and there, a couple of days’ cooling off. Taneyev, in fact, was the soloist for the Moscow premiere of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, and gave the Russian premiere of the Second as well as the world premiere of the Third.

Their outlook was indeed similar, and after Tchaikovsky’s death Taneyev completed and edited some of the unfinished works. Searching for a more international or cosmopolitan expression, they had not bought into the Russianism of Balakirev or Mussorgsky. But Taneyev’s Suite de Concert, really a violin concerto, is his most famous work, and is filled with, ironically, folk-like beauty. A heart attack killed him as he recuperated from pneumonia he caught attending the funeral of another world-famous composer, Scriabin. 1915 was certainly a year of upheaval.

PROGRAM:

Émile Waldteufel (1837-1915): The Skater Waltz (1882)

Sergei Taneyev (1856-1915): Suite de concert (1909)

You know you wanted to see André Rieu play Émile Waldteufel's Skater Waltz, complete with brass section shenanigans:

http://youtu.be/U_J33Q--Tz4